Simon Schaffer: plastičnost znanosti in zgodovinarsko življenje

V RKHV intervjuju smo gostili Simona Schafferja, profesorja na Oddelku za zgodovino in filozofijo znanosti Univerze v Cambridgeu. V svoji več kot štiridesetletni karieri je napisal vrsto člankov ter sodeloval pri pripravi serije dokumentarcev in razstav, ki obravnavajo različne izseke iz zgodovine znanosti med 16. in 19. stoletjem. Med drugim se je ukvarjal s preobrazbo astronomije v kontekstu Britanske Indije, mehanizacijo v času industrijske revolucije in eksperimentalnimi praksami v zgodnji moderni. Izhajajoč iz teh zgodovinskih primerov se osredotoča na širšo vlogo inštrumentov, standardizacije, meroslovja, discipline in organizacije lokalnih znanstvenih »delovišč« pri proizvajanju znanstvene vednosti.

Njegovo delo se najpogosteje povezuje s sociologijo znanstvene vednosti ali sociology of scientific knowledge, običajno okrajšano kot SSK. Začetki gibanja SSK segajo v sedemdeseta, ko sta bili na univerzah v Edinburgu in Bathu vzporedno ustanovljeni raziskovalni skupini, ki sta se zavzemali za tako imenovani strong programme ali močni program v sociologiji znanosti. Jedro teh raziskav je bilo stališče, da je treba za proučevanje ovrženih in veljavnih znanstvenih teorij ubrati enak pristop, ki znanost kot posebno obliko vednosti oziroma kulture pojasnjuje prek konkretnih družbenih okoliščin njenega nastanka. V tem oziru so zgodovinarji-sociologi prelomili s prejšnjim sporom med internalisti in eksternalisti, ki je bil značilen za anglo-ameriško zgodovino znanosti v času hladne vojne. Internalisti, med katere se recimo prišteva Herberta Butterfielda ali Thomasa Kuhna, so zlasti pod vplivom Alexandra Koyréja zgodovino znanosti videli kot sekvenco miselnih sprememb, strogo ločenih od ekonomskih ali političnih dejavnikov. Eksternalisti, na primer Robert Merton ali marksistični zgodovinar John Desmond Bernal, so po drugi strani preobrazbe v znanosti povezovali z njenimi družbenimi funkcijami. Nezadovoljni s prepadom med tema poloma so zgodovinarji iz vrst SSK poudarili vzajemno prepletenost znanstvenih institucij, družbenih praks in teorij, skovanih v teh okvirih. Ali kot sta ta program strnila Schaffer in Steven Shapin v svoji sloviti knjigi Leviatan in zračna tlačilka: »Rešitve problemov vednosti so vedno tudi rešitve problemov družbenega reda.«

V intervjuju za Radio Študent je Simon Schaffer najprej opisal institucionalne premike v britanskem akademskem prostoru, ki so spremljali začetke SSK.

In the 1970s, significantly, a group of sociologists of very different backgrounds – in the United Kingdom, principally – began to use, in rather systematic ways, historical material taken from the past of the sciences as part of their analysis of the conduct of scientific practice. So, that was already extremely interesting for people who were being trained or working in areas like history of science at that time because of this rather unfamiliar experience of being in conversation with people with a background in the social sciences. So, there was already, I would say, an interesting disciplinary conversation within the universities; I mean that was absolutely an academic conversation. And then there was also a methodological implication, which is very interesting – at least I hope it's very interesting – which is that the thought that the past of the sciences was up for sociological analysis also had major effects on the kinds of stories historians of science began to tell. We're talking about very small communities of researchers and scholars here of comparatively low or very low disciplinary status – that’s already interesting. These are not, by and large, public intellectuals or people with very serious status within the universities.

Katere ključne prelome je SSK uvedla v načinu pisanja zgodovine znanosti?

The changes within the kinds of narratives that historians of science began to tell were quite dramatic. I would pick out three in particular. One, controversy stopped being an embarrassment. Roughly speaking, until at least then, until at least the 1970s, it was imagined that the default condition in the sciences was agreement and if there was a major controversy, then something external to the sciences must be at play. So, the places where you looked for the political or the ideological affecting the sciences was where there was disagreement. Because normally, so it had been assumed, scientists would always agree with each other. Because there’s only one nature, and everyone’s wired up the same way, and everyone uses the same equipment, so you’d expect everyone to hold to the same results. And if they don’t, it must be because of their religion, or their politics, or their nationality. That was what had been claimed. And the advent of SSK meant that the exact opposite would now be assumed. That what was to be explained was why any groups agreed with each other. First of all, what is it that makes a group maintain its own culture and practices. That needs explanation because it’s not inertial. And secondly, what is the relation between different groups and rather than treat that as an embarrassment it became a highly productive research site.

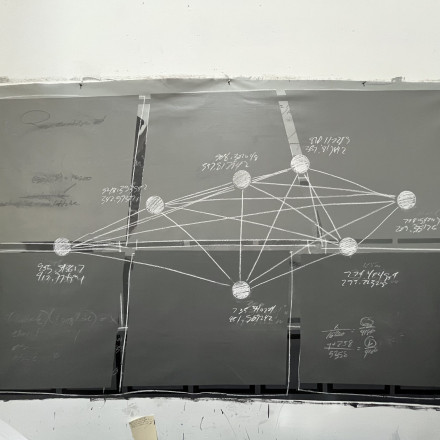

Second change, a hugely important function of historians of science until then had been to sort out priority. So that the chronicles that historians of science told each other – and told the scientists – were precisely chronicles, they were date lists. Sometimes literally so. That a history of science was essentially a timeline and the job of the historian of science was to assign priority of discovery in good order to the heroes and heroines of the past of the sciences. And instead of that profoundly chronological, chronical ordered form of history, I think the effect of SSK was to make geography the pattern. And so the question stopped being, who did what first, and started to become the fascinating question, how does what works in one place work anywhere else? And obviously that led to the use of terms like network, map, chart, and so on, and made issues like replication really significant.

And the third and perhaps most obvious, perhaps rather superficial change, because this is a change that had happened decades if not centuries earlier in most social sciences, was a switch from theory to practice. So that what was going to be analysed by people thinking about the past of the sciences was what scientists did, much more than what they said. The unit of analysis therefore became bits and pieces of practical action and that meant changing, or at least adding to, the kinds of methods that historians of science were going to be using. You couldn’t any longer simply rely on public texts, you had to look much more closely at letters and notebooks, at informal kinds of publication. To put it bluntly, historians of science started to read the newspapers. And they started to read the letters, and they started to see if it was possible to re-enact experiments or practices or observations that past scientists had done. And all those activities were engaged in, in order to see if it was possible to recapitulate and get a better handle on past scientific practice.

Sogovorca smo podrobneje vprašali o prijemih, ki jih je SSK ubrala pri raziskovanju replikabilnosti oziroma družbenih tehnologij in procesov, ki posamezne lokalne poskuse, opažanja, meritve in objekte pretvorijo v ponovljive, prenosljive in posledično univerzalne znanstvene inštrumente, praktike, metode in rezultate, pred katerimi se razgrinja domnevno enotna narava.

One of the most important areas of inquiry for SSK from the 1970s onwards, certainly in my work and the work of the people I worked with, was the theme of replication. And it’s really an interesting thing why that’s so important. It’s important because it’s a way of turning what might seem to be an abstract philosophical question into a question of practice. The abstract philosophical question here is the problem of induction, which is: how do scientists know that various aspects of the world that they observe, engage with, recover – collectively – can be, as we say, projected? How do I know that the local experience of the laboratory, or the field station or the clinic – the zoo or the hospital – is representative of more than itself? One of the absolutely fascinating aspects, certainly when I started to work on the practice of scientific experiments in the late 70s, early 80s, was to ask how did it ever come to pass that there were these places so special and these practices so privileged that it was OK to generalise from them, in fact, that was why they were arranged like that. So that the question of the history of the laboratory became absolutely fundamental and, by comparison, the history of the field station and so on. I think that was an enormously important debt that historians of science owed to certain kinds of sociological questions.

Schaffer pojasni, kako je srečanje s sociologijo znanosti preusmerilo njegov lasten pristop.

I did my PhD, finished it in 1980, on the political theology of Isaac Newton. And I managed to write an entire thesis on Newton’s cosmology, astronomy and natural philosophy without talking about any experiments that he performed or any observations that he carried out. I’d written my PhD very much in dialogue with what we might call the sociology of philosophy, rather than the sociology of science. And what I was interested in, in my own thesis, was the relationship between different kinds of cosmologies. A cosmology, in Newton’s case, which made a pretty radical distinction between passive and active matter. And to ask the question about what sort of hierarchy that radical distinction naturalised. So the idea in my PhD, this was a very common way of making this argument, was that there must be some kind of mediation between material that Newton was arguing for in the period when he was composing the Principia, up to 1687, and the Optics, up to 1704, where he was obsessed, so it seemed, by distinctions between what matter and spirit could achieve and arranging them in some kind of God-given, literally God given, hierarchy. And then asking how that related to the political theology of what was after all a revolutionary period in British history, in which Newton played a major part – he was member of parliament and he was head of the Royal Mint, and so on, and so on. But what was completely missing from that inquiry was practice. Newton figures in my PhD as an author, he does not figure as an experimenter or an observer. So the shift that I think the encounter with SSK brought about was to ask about the landscape, the institutional landscape of that sort of work. So I began to think about Robert Boyle’s experiments on matter and spirit and I began to think about Isaac Newton’s experiments on optics and contemporary work on chemistry. And the idea was to use that work as a probe to explore the places, literally the political geography now, of how in cities like Cambridge or London or elsewhere the activity of knowledge making was laid out. So, a shift from doctrinal analysis to something much more like mapping and the nodes of the map would be occupied by sites of labour. I think what lurked underneath this set of questions was a labour theory of knowledge, in which one could make sense of what the sciences were by applying to the labours of the sciences principles which up till then had been applied quite successfully to the organisation of work. So, one question was a set of questions about training and to analyse the puzzle of discipline, at a period when, certainly in England, there was no such thing as natural science. And to notice, one was very much influenced by the work that Michel Foucault had produced in the early to mid-1970s, and this became a programme in Anglo-America by the early 1980s, that wanted to argue for the linkage between the two senses of ‘discipline’. It’s no doubt important that what in French was called Surveillir et Punir, in English was called Discipline and Punish. And in the preface that he wrote for the American edition, Foucault, perhaps quite riskily, had admitted that discipline was probably a better title for the book than surveillance. That is a very interesting conversation to have because in English the two senses of discipline, as a classification of knowledge and as an exercise of bodily corporeal power, are welded together in quite a satisfactory and useful way. So, to ask about the discipline of experiment in the second half of the 17th century is both to ask about the organisation of knowledge and about the exercise of bodily power, both of which are extremely relevant to the conduct of practical inquiry, the work of experiment, in cases like experiments on respiration or experiments on optics. And then the complementary aspect of that was also geographical. But not just to try and characterise better the workplaces of this kind of experiment – literally the layout of the rooms, the institutions of the colleges, of the city, of the shops and streets where this kind of activity was going on – but also how what worked in one place worked elsewhere. And that, as I’ve said, takes us back to the problem of induction. And it turned out that it might be possible to make sense of this rather sterile philosophical problem with the approach of labour history and sociology of knowledge; and that seemed quite exciting.

Kasneje je Schaffer napisal članek o information orders ali informacijskih redih, ki so Newtonu omogočili utemeljitev univerzalne veljavnosti zakonov iz njegovega najbolj znanega dela Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica ali Matematična načela filozofije narave. V svoji študiji jasno pokaže, da se je Newton, ki je sicer svoje življenje preživel v relativno obskurnem angleškem mestecu, opiral na poročila opazovalcev s celega sveta. Med njimi so bile zlasti ključne reportaže o gibanju kometov. Prek informacijskih in trgovinskih kolonialnih mrež je Newton zbral popise iz Brazilije, Kitajske in Marylanda ter na podlagi njih dokazoval eliptično kroženje kometov okoli Sonca. Schafferjeva osrednja poanta oziroma zasuk je, da so bila lokalna potovanja, konkretna opazovanja in globalna infrastruktura, ki je omogočila kroženje in združevanje oddaljenih informacij, nepogrešljivo vpeti v oblikovanje naravoslovne vednosti. Na ta način Newtonove teze, ki se jih velikokrat prikazuje kot abstraktne genialne prebliske, umesti v socialna razmerja, v katerih se je proizvajala naravna filozofija 17. stoletja.

V Schafferjevi misli je mogoče zaslediti vplive različnih kontinentalnih tokov v filozofiji, sociologiji, antropologiji in zgodovini, ki so danes običajno popolnoma izključeni iz anglo-ameriškega znanstvenega zgodovinopisja. Poleg tega, da vpleta francoske zgodovinarje, kot je Marc Bloch, frankfurtsko šolo in Gramscija, se Schaffer pogosto opira na Marxa, zlasti na pojem fetišizma, in Foucaulta. Na kakšen način ta dva teoretika nastopata v njegovem delu?

I think both Marx and Foucault have played absolutely fundamental roles in the sort of work that I’ve been trying to do, certainly in the questions that seemed to me important to ask about the development of the sciences, maybe less so in the answers, if you see what I mean. So, to be a bit more reflexive about this, it’s Foucault, in Questions of Method and other writings, who argues that you should treat these materials as tools and policies, rather than creeds and doctrines. And I think there are important political questions to raise about the way citation works, that’s to say, what is actually going on when scholars wear their intellectual sources on their sleeves. That’s a really interesting and, at least within the academy, important political question. To what extent do different programmes in the human sciences look like sects, or creeds? And to what extent do they rather offer toolkits, bits of practice, select questions? So, the way I was trained – I hope you can see why this is a relevant approach to the answer to your question – the way I was trained was to understand that what binds groups of inquirers together is the questions they share, not the gods they worship and certainly not the books they read. So, I think, what has been really important for the work I’ve tried to do is the puzzles that certainly Marx and certainly Foucault’s work raise for any respectable historical analysis of the sciences. The questions that Foucault raises are questions of discipline, questions of the relation between power and knowledge, and questions of what in some of his later interviews he calls ‘internal colonisation’. There’s a very interesting interview that Foucault had in Japan about the history of theatre, interestingly, in which he, reflecting late in his life on his work, he says that to a certain extent what he’s been concerned with is Western colonisation of the West, is the internal colonisation of European space by European savoir-pouvoir, power-knowledge. And I think that’s a very, very interesting way of thinking about the relationship between the development of the sciences, the labour of technique and the exercise of political power in the period that has concerned me, which is roughly the period 1650 to 1900. Which is precisely the period of transformation from the classical epoch, an epoch where the dominant form of knowledge was natural history and the dominant agent in the manufacture of knowledge was the court, above all, to a conjunction where the agency of imperialism and capital was absolutely the dominant form of expression and development and resourcing of knowledge right through the long 19th century, for Europeans. And the dominant form of knowledge, the dominant discipline was something much more like experimental technoscience. And the long-term question is what are those transformations and who else is involved in them. What I think both Marxian and Foucauldian arguments make one think about is: we need to increase the length of the list of agents involved in the stories we tell. That especially applies to histories of knowledge, where the very term knowledge has that restrictive sense to it. And, secondly, we need to stop thinking of the exercise of power as a purely distorting, parasitic principle that disrupts what would otherwise be the inertial course of the sciences.

Izpostavljanje političnih razmerij, v katerih znanost nastaja, po Schafferjevem mnenju ne ogroža njene veljavnosti. Nasprotno, šele na ta način je proizvajanje specializiranih znanj sploh lahko zadovoljivo pojasnjeno. Tisto, kar neti skepso in razne teorije zarote, so ravno situacije, v katerih se podoba znanstvenega dela kot progresivnega odkrivanja absolutnih, nespornih resnic izkaže za nezadostno in neživljenjsko.

It’s often argued that somehow or other sociology of scientific knowledge made a terrible error. That what it did was constantly call into question the status of science, technology and medicine, and this kind of corrosive relativism, it’s argued, turned into a weapon that the conservatives and the right-wing could then use when their interests were crossed by the sciences, as in the case of the tobacco lobby or the nuclear power lobby or, above all, the debates around human caused climate change. I think that’s a ludicrous argument for many different reasons. And one of the reasons, which is concerning me right now because I’m involved with a project on the history of climate history, based here in Cambridge in [the department of] History of Science and in Geography, is that if you want to make scientific knowledge vulnerable, exaggerate its strengths. It’s precisely the notion that if a knowledge item is scientific, it’s irrefutable, that is the chief weapon in the conservative’s armoury. Corporate exploitation of those moments when scientists look as though they differ from each other or when their knowledge looks anything but absolutely certain, those are the moments that corporate interests exploit. Corporatists are not relativists. They use the exaggerated claims of positivism and it’s the job of STS [Science and Technology Studies] to make the sciences more robust by making them more plastic. We need to get rid of plastic from the oceans and understand how plastic knowledge is.

Za razliko od precejšnjega dela SSK Schafferjevi prispevki izrazito poudarjajo vlogo kolonializma v zahodnem znanstvenem razvoju. Sogovorec zopet vzame samega sebe za svoj zgodovinski objekt in nam pojasni, kaj ga je spodbudilo k razširitvi analize onkraj evropskih zgodovinskih virov.

My own work began to concern itself with studies of material beyond the European space relatively early and for empirical, as well as political reasons. Partly because of the importance of increasing the list and increasing the size of the list of the number of actors and agents involved in the stories about the sciences. That was obviously in response to major political developments in the wake of the Reagan-Thatcher period, so after 1989 that seemed absolutely obvious. Alongside, it must be said, the perhaps more unusual but certainly for me absolutely fundamental development, which was trying to think harder about the genealogy of the methods that we were using. So, as early as the 1970s, after all, it was extremely obvious that one of the principal sources in SSK was anthropology. That was made completely explicit. So, the work of Malinowski or Levi-Strauss or Mary Douglas or Edward Evans-Prichard was absolutely fundamental methodologically for the emergence of sociology of scientific knowledge in Britain. So, on the one hand I started to work on the way in which colonial and imperial resources were built into the structure and conduct of the sciences, within Europe. And on the other hand, the way in which those colonial settings had developed methods that were then the methods that would be used to analyse European science. So, I wrote an essay called From Physics to Anthropology and Back again, which was a talk I gave at the Cambridge Social Anthropology Department, was heavily influenced by an essay by the then leading historian of anthropology George Stocking and which was about the work of Franz Boas and William Rivers.

Eden izmed glavnih razlogov za prepričljivost Schafferjevega argumenta je, da kolonialna razmerja niso samo sporna spremljava ali problematično okolje, v katerem se je ločeno razvijala resnična znanost. Skozi podrobno proučevanje različnih raziskovalnih ekspedicij pokaže, da je bila kolonialna infrastruktura neobhodna za doseganje konkretnih znanstvenih prebojev. Iz eksotične in neobvladljive kolonialne narave, kakor se jo je mnogokrat prikazovalo, so imperialni znanstveniki lahko iztisnili skrite univerzalne zakonitosti šele na podlagi logističnih mrež za prevažanje inštrumentov in sistema opazovalnic, ki so jih Britanci recimo vzpostavili po indijskem teritoriju, kot tudi prek treninga in vključitve lokalnih delavcev v hierarhijo znanstvenih skupin. Schaffer opiše konkreten primer tovrstnega prepleta med kolonializmom in znanostjo.

It was very quickly obvious that there were many examples, not just of the way in which colonial interests had directed the sciences, but the way in which they were present inside the organisation and content of the sciences. So, one example that has obsessed me is the concern of the emergence of a new version of astronomy in the later 19th century, the construction of astrophysics from the 1860s, which for most European and North-American astronomers was absolutely linked fundamentally to questions of imperial and colonial administration. So, in the British case, the example is very clear. British astronomers from the 1860s began to argue that there was a strong relationship between the sunspot cycle and the incidence of monsoons in the Indian Ocean and southern Asia. The data that they were using was data produced by the military dictatorship that the British exercised over south Asia, from Calcutta and Madras. The effects of monsoon failure were spectacularly obvious, both to Indians and to the British, because of the millions of deaths that Indians suffered in the great famines of the 1870s and afterwards. As Mike Davis has shown in his masterpiece, Late Victorian Holocausts, the effects of those failures of supply were essentially naturalised by the scientists. What the scientists were arguing was that famine was the result of a change in the Sun, not, therefore, a result in British administration of India, which it in fact was. And to close that terrible, vicious circle, it was that work that led to the identification, by climatologists and astronomers, of the El Niño effect, the southern pressure oscillation. We now know that those climatic changes are necessary causes of famine, but they are completely insufficient. As Amartya Sen, the great Inidian economist, has pointed out, there has never been a famine in a democracy. So, while the climatic changes the British were studying were absolutely necessary to produce the famines, the reason for the famines, the necessary condition and the sufficient condition for the famine, was British economic policy and the way in which the astrophysics naturalised its effects. And what’s so striking, finally, is that that was recognised at the time. In the late 1800s, Indian politicians argued that what British science was doing, was shifting the responsibility from the British regime to nature. That’s an extremely clear example of the way in which what counts as nature and what counts as society, what counts as policy and what counts as physics, in a colonial and imperial setting, is wrapped up with excellent science and terrible, terrible politics. The institution that the British built at Kodaikanal in southern India, is the observatory that produced some of the decisive evidence for the truth of Einstein’s general theory of relativity, for example. So there’s a very strong relationship there between politics, institution and science and it’s not simply that when bad politics is in operation, the science is distorted. That is not what’s going on in that story, so it’s a story that I keep on coming back to from a many different reasons; quite apart from the brutal fact of the death of millions of Indians as a result of British economic and imperial policy, which is at the very centre of that concern.

Kritika kolonialnih in rasnih razmerij se je letos ponovno pojavila na prvih bojnih črtah političnih gibanj. Glede na to, da se Schafferjevo zgodovinsko delo tesno povezuje z muzejskimi eksponati, razstavami, univerzo in drugimi prostori, v katerih se ustvarjajo kanoni in družbeni spomin, smo ga vprašali, kje sam vidi pomen britanskih protestnih obračunov s kipi?

I think the protests are really important, some of them very important indeed. There’s been one recently in Cambridge around a window in one of the Cambridge colleges that was put up in memory of and in honour of a racist 20th century scientist, of great eminence and significance, R. A. Fisher. As a result of the debates around Fisher’s reputation and memory, the window will now be removed. And that seems to me to be a wholly good thing. In general, these debates are welcome because they focus the right kind of attention on what counts as memory and what counts as canonisation. It’s always too easy for conservative defenders of tradition to insinuate that politics is entirely on the side of those who wish to change things; as though the decision, for example, to erect a statue to Edward Colston, the Bristol merchant, which was a decision taken in the late 1800s, two hundred years after Edward Colston’s life, as though that decision was not political. I think the controversies about the statues and their fate are welcome, finally, because they remind us how important public memory is. And it’s quite easy in some milieux to forget just how important public memory is in organising public conduct, how important the idiom of public memory and public history is, and, therefore, why history is a battlefield or it’s nothing.

V zvezi z mobilizacijskim potencialom epistemologije Schaffer izpostavlja razlike med intelektualno klimo, ki je v Veliki Britaniji v 80-ih letih povezovala širok nabor kritičnih teorij in marksističnega zgodovinopisja, ter današnjimi, bolj specializiranimi in izrazito anglocentričnimi pristopi. Za zaključek nam zaupa, kako razume aktualni razvoj britanskega akademskega prostora in političnega delovanja v njem.

I think, and I’m not the only person to think this, I think there has been a pretty grim set of developments around specialisation and around the growth of conservative and neoliberal politics. Not only within the institutions of the university, but in the contents of the debates that are conducted there, at least in the United Kingdom that’s absolutely true, and I’ve also noticed this in Germany and in France, which are the two other European countries whose scholarship I’m most familiar with. So that on the one hand, to be put it very crudely and in ways that are extremely familiar, colleagues are supposed to be treated as though they were competitors and students are treated as though they were supposed to be customers. Now that would be bad enough. But it also goes along with the, I think, massive weakening and undermining, and in some cases explicit undermining, of programmes that aim at forms of criticism or transformation or critique more generally. And it’s pretty easy to see how that’s happened, not so easy to see ways in which it can be resisted. There are nevertheless sources for major optimism. The most important of which is the massive growth and intensification of extremely significant and extremely sophisticated, and very highly mobilised forms of debate and analysis – among students and colleagues – around issues like the politics of identity, the politics of race, around the climate emergency, and so on. What might be troubling or, at least, what we clearly might need is the development of resources that allow the better reflection on and coordination between those kinds of groupings and initiatives. So, on the one hand, over the last half century, I think there’s been a weakening of programmatic and engaged scholarship in the human sciences in this country, while at the same time there’s been a massive intensification of political activity and of well-informed intervention in and debates about issues that really matter, whether they’re issues about symbolic and real violence, issues about exclusion, issues about racism and gender prejudice and violence – all of those have intensified and developed, it seems to me, in highly progressive ways. But what I’m saying is that that has not been accompanied by an equivalent response that has allowed the formulation of ways of thinking about knowledge and power that do justice to what’s changed. And that’s a self-criticism, right? That was our job and we failed.

Dodaj komentar

Komentiraj