FOXTOPUS

and the extinct Ammonoidea.[126] They have eight limbs like other Coleoidea, but lack the extra specialised feeding appendages known as tentacles which are longer and thinner with suckers only at their club-like ends.[127] The vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis) also lacks tentacles but has sensory filaments.[128]

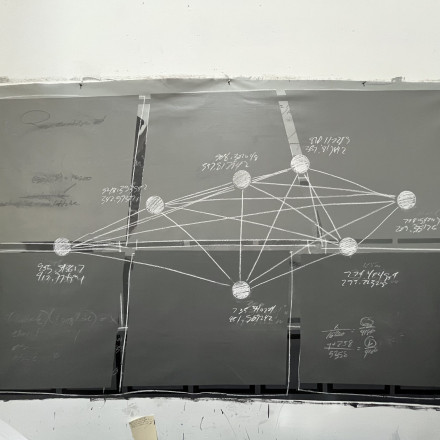

The cladograms are based on Sanchez et al., 2018, who created a molecular phylogeny based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA marker sequences.[121] The position of the Eledonidae is from Ibáñez et al., 2020, with a similar methodology.[129] Dates of divergence are from Kröger et al., 2011 and Fuchs et al., 2019.[124][123]

Cephalopods

Nautiloids

Nautilus A spiral nautilus in a blue sea

Coleoids

Decabrachia

Squids and cuttlefish A squidVampyropoda

Vampyromorphida

A stran structure of the gills allows for a high oxygen uptake, up to 65% in water at 20 °C (68 °F).[44] Water flow over the gills correlates with locomotion, and an octopus can propel its body when it expels water out of its siphon.[43][41]

The thin skin of the octopus absorbs additional oxygen. When resting, around 41% of an octopus's oxygen absorption is through the skin. This decreases to 33% when it swims, as more water flows over the gills; skin oxygen uptake also increases. When it is resting after a meal, absorption through the skin can drop to 3% of its total oxygen uptake.[45]

Digestion and excretion

The digestive system of the octopus begins with the buccal mass which consists of the mouth with its chitinous beak, the pharynx, radula and salivary glands.[46] The radula is a spiked, muscular tongue-like organ with multiple rows of tiny teeth.[30] Food is broken down and is forced into the oesophagus by two lateral extensions of the esophageal side walls in addition to the radula. From there it is transferred to the gastrointestinal tract, which is mostly suspended from the roof of the mantle cavity by numerous membranes. The tract consists of a crop, where the food is stored; a stomach, where food is ground down; a caecum where the now sludgy food is sorted into fluids and particles and which plays an important role in absorption; the digestive gland, where liver cells break down and absorb the fluid and become "brown bodies"; and the intestine, where the accumulated waste is turned into faecal ropes by secretions and blown out of the funnel via the rectum.[46]

ad foxes in Carbunup

Foxes are often considered pests or nuisance creatures for their opportunistic attacks on poultry and other small livestock. Fox attacks on humans are not common.[35] Many foxes adapt well to human environments, with several species classified as "resident urban carnivores" for their ability to sustain populations entirely within urban boundaries.[36] Foxes in urban areas can live longer and can have smaller litter sizes than foxes in non-urban areas.[36] Urban foxes are ubiquitous in Europe, where they show altered behaviors compared to non-urban foxes, including increased population density, smaller territory, and pack foraging.[37] Foxes have been introduced in numerous locations, with varying effects on indigenous flora and fauna.[38]

In some countries, foxes are major predators of rabbits and hens. Population oscillations of these two species were the first nonlinear oscillation studied and led to the derivation of the Lotka–Volterra equation.[39][40]

Hunting

Main article: Fox hunting

Fox hunting originated in the United Kingdom in the 16th century. Hunting with dogs is now banned in the United Kingdom,[41][42][43][44] though hunting without dogs is still permitted. Red foxes were introduced into Australia in the early 19th century for sport, and have since become widespread through much of the country. They have caused population decline among many native species and prey on livestock, especially new lambs.[45] Fox hunting is practiced as recreation in several other countries including Canada, France, Ireland, Italy, Russia, United States and Australia.

Domestication

A tame fox in Talysarn, Wales

See also: Domesticated silver fox and Red fox § Taming and domestication

There are many records of domesticated red foxes and others, but rarely of sustained domestication. A recent and notable exception is the Russian silver fox,[46] which resulted in visible and behavioral changes, and is a case study of an animal population modeling according to human domestication needs. The current group of domesticated silver foxes are the result of nearly fifty years of experiments in the Soviet Union and Russia to domesticate the silver morph of the red fox. This selective breeding resulted in physical and behavioral traits appearing that are frequently seen in domestic cats, dogs, and other animals, such as pigmentation changes, floppy ears, and curly tails.[47] Notably, the new foxes became more tame, allowing themselves to be petted, whimpering to get attention and sniffing and licking their caretakers.[48]

Attack

Main article: Animal attack

In 2018, a Clapham fox bit a woman on the arm after she had left the door to her flat open.[49]

Urban settings

See also: Red fox § Urban red foxes

Foxes are among the comparatively few mammals which have been able to adapt themselves to a certain degree to living in urban (mostly suburban) human environments. Their omnivorous diet allows them to survive on discarded food waste, and their skittish and often nocturnal nature means that they are often able to avoid detection, despite their larger size.U

In Asian folklore, foxes are depicted as familiar spirits possessing magic powers. Similar to in Western folklore, foxes are portrayed as mischievous, usually tricking other people, with the ability to disguise as an attractive female human. Others depict them as mystical, sacred creatures who can bring wonder and/or ruin.[51] Nine-tailed foxes appear in Chinese folklore, literature, and mythology, in which, depending on the tale, they can be a good or a bad omen.[52] The motif was eventually introduced from Chinese to Japanese and Korean cultures.[53]

The constellation Vulpecula represents a fox.[54]

Flexible biomimetic 'Octopus' robotics arm. The BioRobotics Institute, Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna, Pisa, 2011[165]

Octopuses offer many possibilities in biological research, including their ability to regenerate limbs, change the colour of their skin, behave intel

During osmoregulation, fluid is added to the pericardia of the branchial hearts. The octopus has two nephridia (equivalent to vertebrate kidneys) which are associated with the branchial hearts; these and their associated ducts connect the pericardial cavities with the mantle cavity. Before reaching the branchial heart, each branch of the vena cava expands to form renal appendages which are in direct contact with the thin-walled nephridium. The urine is first formed in the pericardial cavity, and is modified by excretion, chiefly of ammonia, and selective absorption from the renal appendages, as it is passed along the associated duct and through the nephridiopore into the mantle cavity.[26][47]

0:31

A common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) moving around. Its nervous system allows the arms to move with some autonomy.

Nervous system and senses

Octopuses (along with cuttlefish) have the highest brain-to-body mass ratios of all invertebrates;[48] this is greater than that of many vertebrates.[49] Octopuses have the same jumping genes that are active in the human brain, implying an evolutionary convergence at molecular level.[50] The nervous system is complex, only part of which is localised in its brain, which is contained in a cartilaginous capsule.[51] Two-thirds of an octopus's neurons are in the nerve cords of its arms; these are capable of complex reflex actions without input from the brain.[52] Unlike vertebrates, the complex motor skills of octopuses are not organised in their brains via internal somatotopic maps of their bodies.[53]

Close up of an octopus showing its eye and an arm with suckers

Eye of common octopus

Like other cephalopods, octopuses have camera-like eyes,[48] and can distinguish the polarisation of light. Colour vision appears to vary from species to species, for example being present in O. aegina but absent in O. vulgaris.[54] Opsins in the skin respond to different wavelengths of light and help the animals choose a coloration that camouflages them; the chromatophores in the skin can respond to light independently of the eyes.[55][56] An alternative hypothesis is that cephalopod eyes in species which only have a single photoreceptor protein may use chromatic aberration to turn monochromatic vision into colour vision, though this sacrifices image quality. This would explain pupils shaped like the letter U, the letter W, or a dumbbell, as well as explaining the need for colourful mating displays.[57]

Attached to the brain are two organs called statocysts (sac-like structures containing a mineralised mass and sensitive hairs), that allow the octopus to sense the orientation of its body. They provide information on the position of the body relative to gravity and can detect angular acceleration. An autonomic response keeps the octopus's eyes oriented so that the pupil is always horizontal.[26] Octopuses may also use the statocyst to hear sound. The common octopus can hear sounds between 400 Hz and 1000 Hz, and hears best at 600 Hz.[58]

Octopuses have an excellent somatosensory system. Their suction cups are equipped with chemoreceptors so they can taste what they touch. Octopus arms move easily because the sensors recognise octopus skin and prevent self-attachment.[59] Octopuses appear to have poor proprioceptive sense and must observe the arms visually to keep track of their position.[60][61]

Ink sac

The ink sac of an octopus is located under the digestive gland. A gland attached to the sac produces the ink, and the sac stores it. The sac is close enough to the funnel for the octopus to shoot out the ink with a water jet. Before it leaves the funnel, the ink passes through glands which mix it with mucus, creating a thick, dark blob which allows the animal to escape from a predator.[62] The main pigment in the ink is melanin, which gives it its black colour.[63] Cirrate octopuses usually lack the ink sac.[37]

Lifecycle

Reproduction

Drawing of a male octopus with one large arm ending in the sexual apparatus

Adult male Tremoctopus violaceus with hectocotylus

Octopuses are gonochoric and have a single, posteriorly-located gonad which is associated with the coelom. The testis in males and the ovary in females bulges into the gonocoel and the gametes are released here. The gonocoel is connected by the gonoduct to the mantle cavity, which it enters at the gonopore.[26] An optic gland creates hormones that cause the octopus to mature and age and stimulate gamete production. The gland may be triggered by environmental conditions such as temperature, light and nutrition, which thus control the timing of reproduction and lifespan.[64][65]

When octopuses reproduce, the male uses a specialised arm called a hectocotylus to transfer spermatophores (packets of sperm) from the terminal organ of the reproductive tract (the cephalopod "penis") into the female's mantle cavity.[66] The hectocotylus in benthic octopuses is usually the third right arm, which has a spoon-shaped depression and modified suckers near the tip. In most species, fertilisation occurs in the mantle cavity.[26]

The reproduction of octopuses has been studied in only a few species. One such species is the giant Pacific octopus, in which courtship is accompanied, especially in the male, by changes in skin texture and colour. The male may cling to the top or side of the female or position himself beside her. There is some speculation that he may first use his hectocotylus to remove any spermatophore or sperm already present in the female. He picks up a spermatophore from his spermatophoric sac with the hectocotylus, inserts it into the female's mantle cavity, and deposits it in the correct location for the species, which in the giant Pacific octopus is the opening of the oviduct. Two spermatophores are transferred in this way; these are about one metre (yard) long, and the empty ends may protrude from the female's mantle.[67] A complex hydraulic mechanism releases the sperm from the spermatophore, and it is stored internally by the female.[26]A female octopus underneath hanging strings of her eggs

Female giant Pacific octopus guarding strings of eggs

About forty days after mating, the female giant Pacific octopus attaches strings of small fertilised eggs (10,000 to 70,000 in total) to rocks in a crevice or under an overhang. Here she guards and cares for them for about five months (160 days) until they hatch.[67] In colder waters, such as those off Alaska, it may take up to ten months for the eggs to completely develop.[68]: 74 The female aerates them and keeps them clean; if left untended, many will die.[69] She does not feed during t directly into the female's mantle cavity, after which he becomes senescent and dies, while the female deposits fertilised eggs in a den and cares for them until they hatch, after which she also dies. Strategies to defend themselves against predators include the expulsion of ink, the use of camouflage and threat displays, the ability to jet quickly through the water and hide, and even deceit. All octopuses are venomous, but only the blue-ringed octopuses are known to be deadly to humans.

Octopuses appear in mythology as sea monsters like the Kraken of Norway and the Akkorokamui of the Ainu, and probably the Gorgon of ancient Greece. A battle with an octopus appears in Victor Hugo's book Toilers of the Sea, inspiring other works such as Ian Fleming's Octopussy. Octopuses appear in Japanese erotic art, shunga. They are eaten and considered a delicacy by humans in many parts of the world, especially the Mediterranean and the Asian seas.

Etymology and pluralisation

See also: Plural form of words ending in -us

The scientific Latin term octopus was derived from Ancient Greek ὀκτώπους, a compound form of ὀκτώ (oktō, "eight") and πούς (pous, "foot"), itself a variant form of ὀκτάπους, a word used for example by Alexander of Tralles (c. 525–c. 605) for the common octopus.[5][6][7] The standard pluralised form of "octopus" in English is "octopuses";[8] the Ancient Greek plural ὀκτώποδες, "octopodes" (/ɒkˈtɒpədiːz/), has also been used historically.[9] The alternative plural "octopi" is considered grammatically incorrect because it wrongly assumes that octopus is a Latin second declension "-us" noun or adjective when, in either Greek or Latin, it is a third declension noun.[10][11]

Historically, the first plural to commonly appear in English language sources, in the early 19th century, is the latinate form "octopi",[12] followed by the English form "octopuses" in the latter half of the same century. The Hellenic plural is roughly contemporary in usage, although it is also the rarest.[13]

Fowler's Modern English Usage states that the only acceptable plural in English is "octopuses", that "octopi"

in red foxes begins in August–September, with the testicles attaining their greatest weight in December–February.[20]

Vixens are in heat for one to six days, making their reproductive cycle twelve months long. As with other canines, the ova are shed during estrus without the need for the stimulation of copulating. Once the egg is fertilized, the vixen enters a period of gestation that can last from 52 to 53 days. Foxes tend to have an average litter size of four to five with an 80 percent success rate in becoming pregnant.[2][21] Litter sizes can vary greatly according to species and environment – the Arctic fox, for example, can have up to eleven kits.[22]

The vixen usually has six or eight mammae.[23] Each teat has 8 to 20 lactiferous ducts, which connect the mammary gland to the nipple, allowing for milk to be carried to the nipple.[citation needed]

Vocalization

The fox's vocal repertoire is vast, and includes:

Whine

Made shortly after birth. Occurs at a high rate when kits are hungry and when their body temperatures are low. Whining stimulates the mother to care for her young; it also has been known to stimulate the male ubmission in the presence of their owners.[2]

Classification

Canids commonly known as foxes include the following genera and species:[2]

Genus Species Picture

Canis Ethiopian wolf, sometimes called the Simien fox or Simien jackal

Ethiopian wolf, native to the Ethiopian highlands

Cerdocyon Crab-eating fox

Crab-eating fox, a South American species

† Dusicyon Extinct genus, including the Falkland Islands wolf, sometimes known as the Falklands Islands fox Falkland Islands wolf Illustration by John Gerrard Keulemans (1842–1912)

Lycalopex

Culpeo or Andean fox

Gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), in Midtown,

hydrothermal vents at 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[29] The cirrate species are often free-swimming and live in deep-water habitats.[38] Although several species are known to live at bathyal and abyssal depths, there is only a single indisputable record of an octopus in the hadal zone; a species of Grimpoteuthis (dumbo octopus) photographed at 6,957 m (22,825 ft).[75] No species are known to live in fresh water.[76]Behaviour and ecology

Most species are solitary when not mating,[77] though a few are known to occur in high densities and with frequent interactions, signaling, mate defending and eviction of individuals from dens. This is likely the result of abundant food supplies combined with limitedthan pull. As progress is made, other arms move ahead to repeat these actions and the original suckers detach. During crawling, the heart rate nearly doubles, and the animal requires ten or fifteen minutes to recover from relatively minor exercise.[32]Most octopuses swim by expelling a jet of water from the mantle through the siphon into the sea. The physical principle behind this is that the force required to accelerate the water through the orifice produces a reaction that propels the octopus in the opposite direction.[92] The direction of travel depends on the orientation of the siphon. When swimming, the head is at the front and the siphon is pointed backward but, when jetting, the visceral hump leaJurassic. The earliest octopus likely lived near the sea floor (benthic to demersal) in shallow marin

The infundibulum provides adhesion while the acetabulum remains free, and muscle contractions allow for attachment and detachment.[34][35] Each of the eight arms senses and responds to light, allowing the octopus to control the limbs even if its head is obscured.[36]

A stubby round sea-creature with short ear-like fins

A finned Grimpoteuthis species with its atypical octopus body plan

The eyes of the octopus are large and at the top of the head. They are similar in structure to those of a fish, and are enclosed in a cartilaginous capsule fused to the cranium. The cornea is formed from a translucent epidermal layer; the slit-shaped pupil forms a hole in the iris just behind the cornea. The lens is suspended behind the pupil; photoreceptive retinal cells cover the back of the eye. The pupil can be adjusted in size; a retinal pigment screens incident light in bright conditions.[26]

Some species differ in form from the typical octopus body shape. Basal species, the Cirrina, have stout gelatinous bodies with webbing that reaches near the tip of their arms, and two large fins above the eyes, supported by an internal shell. Fleshy papillae or cirri are found along the bottom of the arms, and the eyes are more developed.[37][38]

Circulatory system

Octopuses have a closed circulatory system, in which the blood remains inside blood vessels. Octopuses have three hearts; a systemic or main heart that circulates blood around the body and two branchial or gill hearts that pump it through each of the two gills. The systemic heart is inactive when the animal is swimming and thus it tires quickly and prefers to crawl.[39][40] Octopus blood contains the copper-rich protein haemocyanin to transport

Darwin's fox

South American gray fox

Pampas fox

Sechuran fox

Hoary fox

A pampas fox in Departamento de Flores, Uruguay

Otocyon Bat-eared fox

Bat-eared fox in Kenya

Urocyon

Gray fox

Island fox

Cozumel fox (undescribed)

oxygen. This makes the blood very viscous and it requires considerable pressure to pump it around the body; octopuses' blood pressures can exceed 75 mmHg (10 kPa).[39][40][41] In cold conditions with low oxygen levels, haemocyanin transports oxygen more efficiently than haemoglobin. The haemocyanin is dissolved in the plasma instead of being carried within blood cells, and gives the blood a bluish colour.[39][40]The systemic heart has muscular contractile walls and consists of a single ventricle e environments.[124][125][123] Octopuses consist mostly of soft tissue, and so fossils are relatively rare. As soft-bodied cephalopods, they lack the external shell of most molluscs, including other cephalopods like the nautiloids

Opisthoteuthidae Opisthoteuthis californiana (white background).jpg

Cirroctopodidae Cirroctopus mawsoni Vent.jpg

Octopodida

"Argonautoidea" part

Tremoctopodidae Pelagic octopus Tremoctopus.jpg

Alloposidae Haliphron atlanticus (70 mm ML).jpg

"Argonautoidea" part

Argonautidae Argonauta argo Merculiano.jpg

Ocythoidae Ocythoe tuberculata (Merculiano).jpg

Octopodoidea

Eledonidae Eledone cirrhosa1.jpg

Bathypolypodidae Bathypolypus valdiviae.jpg

Enteroctopodidae E zealandicus (white background).jpg

Octopodidae Octopus vulgaris Merculiano.jpg

Megaleledonidae Graneledone boreopacifica (white background).jpg

Bolitaenidae Eledonella pygmaea.jpg

Amphitretidae Amphitretus pelagicus.jpg

Vitreledonellidae Vitreledonella richardi (white background).jpgRNA editing and the genome

Octopuses, like other coleoid cephalopods but unlike more basal cephalopods or other molluscs, are capable of greater RNA editing, changing the nucleic acid sequence of the primary transcript of RNA molecules, than any other organisms. Editing is concentrated in the nervous system, and affects proteins involved in neural excitability and neuronal morphology. More than 60% of RNA transcripts for coleoid brains are recoded by editing, compared to less than 1% for a human or fruit fly. Coleoids rely mostly on ADAR enzymes for RNA editing, which requires large double-stranded RNA structures to flank the editing sites. Both the structures and editing sites are conserved in the coleoid genome and the mutation rates for the sites are severely hampered. Hence, greater transcriptome plasticity has come themselves, be caught as bycatch if they cannot get away.[160]

In science and technology

In classical Greece, Aristotle (384–322 BC) commented on the colour-changing abilities of the octopus, both for camouflage and for signalling, in his Historia animalium: "The octopus ... seeks its prey by so changing its colour as to render it like the colour of the stones adjacent to it; it does so also when alarmed."[161] Aristotle noted that the octopus had a hectocotyl arm and suggested it might be used in sexual reproduction. This claim was widely disbelieved until

den sites.[78] The LPSO has been described as particularly social, living in groups of up to 40 individuals.[79][80] Octopuses hide in dens, which are typically crevices in rocky outcrops or other hard structures, though some species burrow into sand or mud. Octopuses

ed into a set of flexible, prehensile appendages, known as "arms", that surround the mouth and are attached to each other near their base by a webbed structure.[26] The arms can be described based on side and sequence position (such as L1, R1, L2, R2) and divided into four pairs.[27][26] The two rear appendages are generally used to walk on the sea floor, while the other six are used to forage for food.[28]

e young octopuses hatch.[68]: 75

In laboratory experiments, octopuses can readily be trained to distinguish between different shapes and patterns. They have been reported to practise observational learning,[99] although the validity of these findings is contested.[97] Octopuses have also been observed in what has been described as play: repeatedly releasing bottles or toys into a circular current in their aquariums and then catching them.[100] Octopuses often break out of their aquariums and sometimes into others in search of food.[94][101][102] The veined octopus collects discarded coconut shells, then uses them to build a shelter, an example of tool use.[96]

Camouflage and colour change

0:54

Video of Octopus cyanea moving and changing its colour, shape and texture

Octopuses use camouflage when hunting and to avoid predators. To do this they use specialised skin cells which change the appearance of the skin by adjusting its colour, opacity, or reflectivity. Chromatophores contain yellow, orange, red, brown, or black pigments; most species have three of these colours, while some have two or four. Other colour-changing cells are reflective iridophores and white leucophores.[103] This colour-changing ability is also used to communicate with or warn other octopuses.[104]

Octopuses can create distracting patterns with waves of dark coloration across the body, a display known as the "passing cloud". Muscles in the skin change the texture of the mantle to achieve greater camouflage. In some species, the mantle can take on the spiky appearance of algae; in others, skin anatomy is limited to relatively uniform shades of one colour with limited skin texture. Octopuses that are diurnal and live in shallow water have evolved more complex skin than their nocturnal and deep-sea counterparts.[104]

A "moving rock" trick involves the octopus mimicking a rock and then inching across the open space with a speed matching that of the surrounding water.[105]Defence

An octopus among coral displaying conspicuous rings of turquoise outlined in black against a sandy background

Warning display of greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata)

Aside from humans, octopuses may be preyed on by fishes, seabirds, sea otters, pinnipeds, cetaceans, and other cephalopods.[106] Octopuses typically hide or disguise themselves by camouflage and mimicry; some have conspicuous warning coloration (aposema

The bulbous and hollow mantle is fused to the back of the head and is known as the visceral hump; it contains most of the vital organs.[29][30] The mantle cavity has muscular walls and contains the gills; it is connected to the exterior by a funnel or siphon.[26][31] The mouth of an octopus, located underneath the arms, has a sharp hard beak.[30]

Schematic of external anatomy

Diagram of octopus from side, with gills, funnel, eye, ocellus (eyespot), web, arms, suckers, hectocotylus and ligula labelled.

The skin consists of a thin outer epidermis with mucous cells and sensory cells, and a connective tissue dermis consisting largely of collagen fibres and various cells allowing colour change.[26] Most of the body is made of soft tissue allowing it to lengthen, contract,

snails because they are too large and limpets, rock scallops, chitons and abalone, because they are too securely fixed to the rock.[83] Small cirrate octopuses such as those of the genera Grimpoteuthis and Opisthoteuthis typically prey on polychaetes, copepods, amphipods and isopods.[86]

A benthic (bottom-dwelling) octopus typically moves among the rocks and feels through the crevices. The creature may make a jet-propelled pounce on prey and pull it toward the mouth with its arms, the suckers restraining it. Small prey may be completely trapped by the webbed structure. Octopuses usually inject crustaceans like crabs with a paralysing saliva then dismember them with their beaks.[85][87] Octopuses feed on shelled molluscs either by forcing the

In adults, the explosive call becomes an open-mouthed combative call during any conflict; a sharper bark.

Growl

An adult fox's indication to their kits to feed or head to the adult's location.

Bark

Adult foxes warn against intruders and in defense by barking.[2][24]

In the case of domesticated foxes, the whining seems to remain in adult individuals as a sign of excitement and s

416 mya

530 mya

The molecular analysis of the octopods shows that the suborder Cirrina (Cirromorphida) and the superfamily Argonautoidea are paraphyletic and are broken up; these names are shown in quotation marks and italics on the cladogram.

Octopoda

"Cirromorphida" part

Cirroteuthidae CirrothaumaMurDraw2.jpg

Stauroteuthidae Stauroteuthis syrtensis (main).jpg

"Cirromorphida" part An octopus (pl: octopuses or octopodes, see below for variants) is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda (/ɒkˈtɒpədə/, ok-TOP-ə-də[3]). The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like other cephalopods, an octopus is bilaterally symmetric with two eyes and a beaked mouth at the center point of the eight limbs.[a] The soft body can radically alter its shape, enabling octopuses to squeeze through small gaps. They trail their eight appendages behind them as they swim. The siphon is used both for respiration and for locomotion, by expelling a jet of water.

his time and dies soon after. Males become senescent and die a few weeks after mating.[64]

The eggs have large yolks; cleavage (division) is superficial and a germinal disc develops at the pole. During gastrulation, the margins of this grow down and surround the yolk, forming a yolk sac, which eventually forms part of the gut. The dorsal side of the disc grows upward and forms the embryo, with a shell gland on its dorsal surface, gills, mantle and eyes. The arms and funnel develop as part of the foot on the ventral side of the disc. The arms later migrate upward, coming to form a ring around the funnel and mouth. The yolk is gradually absorbed as the embryo develops.[26]

A microscopic view of a small round-bodied transparent animal with very short arms

Octopus paralarva, a planktonic hatchling

Most young octopuses hatch as paralarvae and are planktonic for weeks to months, depending on the species and water temperature. They feed on copepods, arthropod larvae and other zooplankton, eventually settling on the ocean floor and developing directly into adults

are not territorial but generally remain in a home range; they may leave in search of food. They can navigate back to a den without having to retrace their outward route.[81] They are not migratory.[82]

Octopuses bring captured prey to the den, where they can eat it safely. Sometimes the octopus catches more prey than it can eat, and the den is often surrounded by a midden of dead and uneaten food items. Other creatures, such as fish, crabs, molluscs and echinoderms, often share the den with the octopus, either because they have arrived as scavengers, or because they have survived capture.[83] On rare occasions, octopuses hunt cooperatively with other species, with fish as their partners. They regulate the species composition of the hunting group — and the behavior of their partners — by punching them.[84]

Feeding

An octopus in an open seashell on a sandy surface, surrounding a small crab with the suckers on its arms

Veined octopus eating a crab

Nearly all octopuses are predatory; bottom-dwelling octopuses eat mainly crustaceans, polychaete worms, and other molluscs such as whelks and clams; open-ocean octopuses eat mainly prawns, fish and other cephalopods.[85] Major items in the diet of the giant Pacific octopus include bivalve molluscs such as the cockle Clinocardium nuttallii, clams and scallops and crustaceans such as crabs and spider crabs. Prey that it is likely to reject include moon

ictionary and Webster's New World College Dictionary. The Oxford English Dictionary lists "octopuses", "octopi", and "octopodes", in that order, reflecting frequency of use, calling "octopodes" rare and noting that "octopi" is based on a misunderstanding.[17] The New Oxford American Dictionary (3rd Edition, 2010) lists "octopuses" as the only acceptable pluralisation, and indicates that "octopodes" is still occasionally used, but that "octopi" is incorrect.[18]

Anatomy and physiology

Size

See also: Cephalopod size

Captured specimen of a giant octopus

A giant Pacific octopus at Echizen Matsushima Aquarium, Japan

The giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) is often cited as the largest known octopus species. Adults usually weigh around 15 kg (33 lb), with an arm span of up to 4.3 m (14 ft).[19] The largest specimen of this species to be scientifically documented was an animal with a live mass of 71 kg (157 lb).[20] Much larger sizes have been claimed for the giant Pacific octopus:[21] one specimen was recorded as 272 kg (600 lb) with an arm span of 9 m

ge blood-red octopus, its arms joined by a web

Octopods

A brown octopus with wriggly arms155 mya

276 myafox into caring for his mate and kits.

Yelp

Made about 19 days later. The kits' whining turns into infantile barks, yelps, which occur heavily during play.

Explosive call

At the age of about one month, the kits can emit an explosive call which is intended to be threatening to intruders or other cubs; a high-pitched howl.

Combative call order of octopuses in 1818 by English biologist William Elford Leach,[119] who classified them as Octopoida the previous year.[2] The Octopoda consists of around 300 known speci

uses have a complex nervous system and excellent sight, and are among the most intelligent and behaviourally diverse of all invertebrates.

Octopuses inhabit various regions of the ocean, including coral reefs, pelagic waters, and the seabed; some live in the intertidal zone and others at abyssal depths. Most species grow quickly, mature early, and are short-lived. In most species, the male uses a specially adapted arm to deliver a bundle of sperm

Octop14][15][16] the last is nonetheless used frequently enough to be acknowledged by the descriptivist Merriam-Webster 11th Collegiate D and contort itself. The octopus can squeeze through tiny gaps; even the larger species can pass through an opening close to 2.5 cm (1 in) in diameter.[30] Lacking skeletal support, the arms work as muscular hydrostats and contain longitudinal, transverse and circular muscles around a central axial nerve. They can extend and contract, twist to left or right, bend at any place in any direction or be held rigid.[32][33]

The interior surfaces of the arms are covered with circular, adhesive suckers. The suckers allow the octopus to anchor itself or to manipulate objects. Each sucker is usually circular and bowl-like and has two distinct parts: an outer shallow cavity called an infundibulum and a central hollow cavity called an acetabulum, both of which are thick muscles covered in a protective chitinous cuticle. When a sucker attaches to a surface, the orifice between the two structures is sealed.

and two atria, one for each side of the body. The blood vessels consist of arteries, capillaries and veins and are lined with a cellular endothelium which is quite unlike that of most other invertebrates. The blood circulates through the aorta and capillary system, to the vena cavae, after which the blood is pumped through the gills by the branchial hearts and back to the main heart. Much of the venous system is contractile, which helps circulate the blood.[26]

Respiration

An octopus on the seabed, its siphon protruding near its eye

Octopus with open siphon. The siphon is used for respiration, waste disposal and discharging ink.

Respiration involves drawing water into the mantle cavity through an aperture, passing it through the gills, and expelling it through the siphon. The ingress of water is achieved by contraction of radial muscles in the mantle wall, and flapper valves shut when strong circular muscles force the water out through the siphon.[42] Extensive connective tissue lattices support the respiratory muscles and allow them to expand the respiratory chamber.[43] The lamella

(30 ft).[22] A carcass of the seven-arm octopus, Haliphron atlanticus, weighed 61 kg (134 lb) and was estimated to have had a live mass of 75 kg (165 lb).[23][24] The smallest species is Octopus wolfi, which is around 2.5 cm (1 in) and weighs less than 1 g (0.035 oz).[25]External characteristics

The octopus is bilaterally symmetrical along its dorso-ventral (back to belly) axis; the head and foot are at one end of an elongated body and function as the anterior (front) of the animal. The head includes the mouth and brain. The foot has evolvwith no distinct metamorphoses that are present in other groups of mollusc larvae.[26] Octopus species that produce larger eggs – including the southern blue-ringed, Caribbean reef, California two-spot, Eledone moschata[70] and deep sea octopuses – instead hatch as benthic animals similar to the adults.[68]: 74–75

In the argonaut (paper nautilus), the female secretes a fine, fluted, papery shell in which the eggs are deposited and in which she also resides while floating in mid-ocean. In this she broods the young, and it also serves as a buoyancy aid allowing her to adjust her depth. The male argonaut is minute by comparison and has no shell.[71]

Lifespan

Octopuses have a relatively short lifespan; some species live for as little as six months. The Giant Pacific octopus, one of the two largest species of octopus, may live for as much as five years. Octopus lifespan is limited by reproduction.[72] For most octopuses the last stage of their life is called senescence. It is the breakdown of cellular function without repair or replacement. For males, this typically begins after mating. Senescence may last from weeks to a few months, at most. For females, it begins when they lay a clutch of eggs. Females will spend all their time aerating and protecting their eggs until they are ready to hatch. During senescence, an octopus does not feed and quickly weakens. Lesions begin to form and the octopus literally degenerates. Unable to defend themselves, octopuses often fall prey to predators.[73] The larger Pacific striped octopus (LPSO) is an exception, as it can reproduce repeatedly over a life of around two years.[72]

Octopus reproductive organs mature due to the hormonal influence of the optic gland but result in the inactivation of their digestive glands. Unable to feed, the octopus typically dies of starvation.[73] Experimental removal of both optic glands after spawning was found to result in the cessation of broodiness, the resumption of feeding, increased growth, and greatly extended lifespans. It has been proposed that the naturally short lifespan may be functional to prevent rapid overpopulation.[74]

Distribution and habitat

An octopus nearly hidden in a crack in some coral

Octopus cyanea in Kona, Hawaii

Octopuses live in every ocean, and different species have adapted to different marine habitats. As juveniles, common octopuses inhabit shallow tide pools. The Hawaiian day octopus (Octopus cyanea) lives on coral reefs; argonauts drift in pelagic waters. Abdopus aculeatus mostly lives in near-shore seagrass beds. Some species are adapted to the cold, ocean depths. The spoon-armed octopus (Bathypolypus arcticus) is found at depths of 1,000 m (3,300 ft), and Vulcanoctopus hydrothermalis lives near

activities to destroy or isolate the pathogens. The haemocytes play an important role in the recognition and elimination of foreign bodies and wound repair. Captive animals are more susceptible to pathogens than wild ones.[117] A gram-negative bacterium, Vibrio lentus, can cause skin lesions, exposure of muscle and sometimes death.[118]

Evolution

Further information: Evolution of cephalopods

The scientific name Octopoda was first coined and given as the

valves apart, or by drilling a hole in the shell to inject a nerve toxin.[88][87] It used to be thought that the hole was drilled by the radula, but it has now been shown that minute teeth at the tip of the salivary papilla are involved, and an enzyme in the toxic saliva is used to dissolve the calcium carbonate of the shell. It takes about three hours for O. vulgaris to create a 0.6 mm (0.024 in) hole. Once the shell is penetrated, the prey dies almost instantaneously, its muscles relax, and the soft tissues are easy for the octopus to remove. Crabs may also be treated in this way; tough-shelled species are more likely to be drilled, and soft-shelled crabs are torn apart.[89]

Some species have other modes of feeding. Grimpoteuthis has a reduced or non-existent radula and swallows prey whole.[37] In the deep-sea genus Stauroteuthis, some of the muscle cells that control the suckers in most species have been replaced with photophores which are believed to fool prey by directing them to the mouth, making them one of the few bioluminescent octopuses.[90]

Locomotion

An octopus swimming with its round body to the front, its arms forming a streamlined tube behind

Octopuses swim with their arms trailing behind.

Octopuses mainly move about by relatively slow crawling with some swimming in a head-first position. Jet propulsion or backward swimming, is their fastest means of locomotion, followed by swimming and crawling.[91] When in no hurry, they usually crawl on either solid or soft surfaces. Several arms are extended forward, some of the suckers adhere to the substrate and the animal hauls itself forward with its powerful arm muscles, while other arms may push rather

the 19th century. It was described in 1829 by the French zoologist Georges Cuvier, who supposed it to be a parasitic worm, naming it as a new species, Hectocotylus octopodis.[162][163] Other zoologists thought it a spermatophore; the German zoologist Heinrich Müller believed it was "designed" to detach during copulation. In 1856 the Danish zoologist Japetus Steenstrup demonstrated that it is used to transfer sperm, and only rarely detaches.[164]

Foxes are small to medium-sized, omnivorous mammals belonging to several genera of the family Canidae. They have a flattened skull, upright, triangular ears, a pointed, slightly upturned snout, and a long bushy tail ("brush").

Twelve species belong to the monophyletic "true fox" group of genus Vulpes. Approximately another 25 current or extinct species are always or sometimes called foxes; these foxes are either part of the paraphyletic group of the South American foxes, or of the outlying group, which consists of the bat-eared fox, gray fox, and island fox.[1]

Foxes live on every continent except Antarctica. The most common and widespread species of fox is the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) with about 47 recognized subspecies.[2] The global distribution of foxes, together with their widespread reputation for cunning, has contributed to their prominence in popular culture and folklore in many societies around the world. The hunting of foxes with packs of hounds, long an established pursuit in Europe, especially in the British Isles, was exported by European settlers to various parts of the New World.

Etymology

The word fox comes from Old English, which derived from Proto-Germanic *fuhsaz[nb 1]. This in turn derives from Proto-Indo-European *puḱ-, meaning ’thick-haired; tail’.[nb 2] Male foxes are known as dogs, tods or reynards, females as vixens, and young as cubs, pups, or kits, though the last name is not to be confused with a distinct species called kit foxes. Vixen is one of very few words in modern English that retain the Middle English southern dialect "v" pronunciation instead of "f" (i.e. northern English "fox" versus southern English "vox").[3] A group of foxes is referred to as a skulk, leash, or earth.[4][5]

Phylogenetic relationships

Comparative illustration of skulls of a true fox (left) and gray fox (right), with differing temporal ridges and subangular lobes indicated

Within the Canidae, the results of DNA analysis shows several phylogenetic divisions:

The fox-like canids, which include the kit fox (Vulpes velox), red fox (Vulpes vulpes), Cape fox (Vulpes chama), Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), and fennec fox (Vulpes zerda).[6]

The wolf-like canids, (genus Canis, Cuon and Lycaon) including the dog (Canis lupus familiaris), gray wolf (Canis lupus), red wolf (Canis rufus), eastern wolf (Canis lycaon), coyote (Canis latrans), golden jackal (Canis aureus), Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis), black-backed jackal (Canis mesomelas), side-striped jackal (Canis adustus), dhole (Cuon alpinus), and African wild dog (Lycaon pictus).[6]

The South American canids, including the bush dog (Speothos venaticus), hoary fox (Lycalopex uetulus), crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) and maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus).[6]

Various monotypic taxa, including the bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis), gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargenteus), and raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides).[6]

Biology

Fox skeleton

General morphology

Foxes are generally smaller than some other members of the family Canidae such as wolves and jackals, while they may be larger than some within the family, such as Raccoon dogs. In the largest species, the red fox, males weigh on average between 4.1 and 8.7 kilograms (9 and 19+1⁄4 pounds),[7] while the smallest species, the fennec fox, weighs just 0.7 to 1.6 kg (1+1⁄2 to 3+1⁄2 lb).[8]

Fox features typically include a triangular face, pointed ears, an elongated rostrum, and a bushy tail. They are digitigrade (meaning they walk on their toes). Unlike most members of the family Canidae, foxes have partially retractable claws.[9] Fox vibrissae, or

ds, the siphon points at the head and the arms trail behind, with the animal presenting a fusiform appearance. In an alternative method of swimming, some species flatten themselves dorso-ventrally, and swim with the arms held out sideways, and this may provide lift and be faster than normal swimming. Jetting is used to escape from danger, but is physiologically inefficient, requiring a mantle pressure so high as to stop the heart from beating, resulting in a progressive oxygen deficit.[91]

Three images in sequence of a two-finned sea creature swimming with an 8-cornered web

Movements of the finned species Cirroteuthis muelleri

Cirrate octopuses cannot produce jet propulsion and rely on their fins for swimming. They have neutral buoyancy and drift through the water with the fins extended. They can also contract their arms and surrounding web to make sudden moves known as "take-offs". Another form of locomotion is "pumping", which involves symmetrical contractions of muscles in their webs producing peristaltic waves. This moves the body slowly.[37]

In 2005, Adopus aculeatus and veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) were found to walk on two arms, while at the same time mimicking plant matter.[93] This form of locomotion allows these octopuses to move quickly away from a potential predator without being recognised.[91] Some species of octopus can crawl out of the water briefly, which they may do between tide pools.[94][95] "Stilt walking" is used by the veined octopus when carrying stacked coconut shells. The octopus carries the shells underneath it with two arms, and progresses with an ungainly gait supported by its remaining arms held rigid.[96]Intelligence

Main article: Cephalopod intelligence

A captive octopus with two arms wrapped around the cap of a plastic container

Octopus opening a container by unscrewing its cap

Octopuses are highly intelligent.[97] Ma in the Cambrian some 530 million years ago. The Coleoidea diverged from the nautiloids in the Devonian some 416 million years ago. In turn, the coleoids (including the squids and octopods) brought their shells inside the body and some 276 million years ago, during the Permian, split into the Vampyropoda and the Decabrachia.[124] The octopuses arose from the Muensterelloidea within the Vampyropoda in the

whiskers, are black. The whiskers on the muzzle, known as mystacial vibrissae, average 100–110 millimetres (3+7⁄8–4+3⁄8 inches) long, while the whiskers everywhere else on the head average to be shorter in length. Whiskers (carpal vibrissae) are also on the forelimbs and average 40 mm (1+5⁄8 in) long, pointing downward and backward.[2] Other physical characteristics vary according to habitat and adaptive significance.

Pelage

Fox species differ in fur color, length, and density. Coat colors range from pearly white to black-and-white to black flecked with white or grey on the underside. Fennec foxes (and other species of fox adapted to life in the desert, such as kit foxes), for example, have large ears and short fur to aid in keeping the body cool.[2][9] Arctic foxes, on the other hand, have tiny ears and short limbs as well as thick, insulating fur, which aid in keeping the body warm.[10] Red foxes, by contrast, have a typical auburn pelt, the tail normally ending with a white marking.[11]

A fox's coat color and texture may vary due to the change in seasons; ze and problem-solving experiments have shown evidence of a memory system that can store both short- and long-term memory.[98] Young octopuses learn nothing from their parents, as adults provide no parental care beyond tending to their eggs until thtism) or deimatic behaviour.[104] An octopus may spend 40% of its time hidden away in its den. When the octopus is approached, it may extend an arm to investigate. 66% of Enteroctopus dofleini in one study had scars, with 50% having amputated arms.[106] The blue rings of the highly venomous blue-ringed octopus are hidden in muscular skin folds which contract when the animal is threatened, exposing the is misconceived, and "octopodes" pedantic;[

es[120] and were historically divided into two suborders, the Incirrina and the Cirrina.[38] More recent evidence suggests Cirrina is merely the most basal species, not a unique clade.[121] The incirrate octopuses (the majority of species) lack the cirri and paired swimming fins of the cirrates.[38] In addition, the internal shell of incirrates is either present as a pair of stylets or absent altogether.[122]Fossil history and phylogeny

Fossil of crown group coleoid on a slab of Jurassic rock from Germany

The octopuses evolved from the Muensterelloidea (fossil pictured) in the Jurassic period.[123]

The Cephalopoda evolved from a mollusc resembling the Monoplacophora

fox pelts are richer and denser in the colder months and lighter in the warmer months. To get rid of the dense winter coat, foxes moult once a year around April; the process begins from the feet, up the legs, and then along the back.[9] Coat color may also change as the individual ages.[2]

Dentition

A fox's dentition, like all other canids, is I 3/3, C 1/1, PM 4/4, M 3/2 = 42. (Bat-eared foxes have six extra molars, totalling in 48 teeth.) Foxes have pronounced carnassial pairs, which is characteristic of a carnivore. These pairs consist of the upper premolar and the lower first molar, and work together to shear tough material like flesh. Foxes' canines are pronounced, also characteristic of a carnivore, and are excellent in gripping prey.[12]

Behaviour

Arctic fox curled up in snow

In the wild, the typical lifespan of a fox is one to three years, although individuals may live up to ten years. Unlike many canids, foxes are not always pack animals. Typically, they live in small family groups, but some (such as Arctic foxes) are known to be solitary.[2][9]

Foxes are omnivores.[13][14] Their diet is made up primarily of invertebrates such as insects and small vertebrates such as reptiles and birds. They may also eat eggs and vegetation. Many species are generalist predators, but some (such as the crab-eating fox) have more specialized diets. Most species of fox consume around 1 kg (2.2 lb) of food every day. Foxes cache excess food, burying it for later consumption, usually under leaves, snow, or soil.[9][15] While hunting, foxes tend to use a particular pouncing technique, such that they crouch down to camouflage themselves in the terrain and then use their hind legs to leap up with great force and land on top of their chosen prey.[2] Using their pronounced canine teeth, they can then grip the prey's neck and shake it until it is dead or can be readily disemboweled.[2]

The gray fox is one of only two canine species known to regularly climb trees; the other is the raccoon dog.[16]

Sexual characteristics

The male fox's scrotum is held up close to the body with the testes inside even after they descend. Like other canines, the male fox has a baculum, or penile bone.[2][17][18] The testes of red foxes are smaller than those of Arctic foxes.[19] Sperm formation

iridescent warning.[107] The Atlantic white-spotted octopus (Callistoctopus macropus) turns bright brownish red with oval white spots all over in a high contrast display.[108] Displays are often reinforced by stretching out the animal's arms, fins or web to make it look as big and threatening as possible.[109]

Once they have been seen by a predator, they commonly try to escape but can also use distraction with an ink cloud ejected from the ink sac. The ink is thought to reduce the efficiency of olfactory organs, which would aid evasion from predators that employ smell for hunting, such as sharks. Ink clouds of some species might act as pseudomorphs, or decoys that the predator attacks instead.[110]

When under attack, some octopuses can perform arm autotomy, in a manner similar to the way skinks and other lizards detach their tails. The crawling arm may distract would-be predators. Such severed arms remain sensitive to stimuli and move away from unpleasant sensations.[111] Octopuses can replace lost limbs.[112]

Some octopuses, such as the mimic octopus, can combine their highly flexible bodies with their colour-changing ability to mimic other, more dangerous animals, such as lionfish, sea snakes, and eels.[113][114]Pathogens and parasites

The diseases and parasites that affect octopuses have been little studied, but cephalopods are known to be the intermediate or final hosts of various parasitic cestodes, nematodes and copepods; 150 species of protistan and metazoan parasites have been recognised.[115] The Dicyemidae are a family of tiny worms that are found in the renal appendages of many species;[116] it is unclear whether they are parasitic or endosymbionts. Coccidians in the genus Aggregata living in the gut cause severe disease to the host. Octopuses have an innate immune system; their haemocytes respond to infection by phagocytosis, encapsulation, infiltration, or cytotoxic Palo Alto, California

Vulpes

Arctic fox

Bengal fox

Blanford's fox

Cape fox

Corsac fox

Fennec fox

Kit fox

Pale fox

at the cost of slower genome evolution.[130][131]

The octopus genome is unremarkably bilaterian except for large developments of two gene families: protocadherins, which regulate the development of neurons; and the C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factors. Many genes specific to cephalopods are expressed in the animals' skin, suckers, and nervous system.[48]

Relationship to humans

An ancient nearly spherical vase with 2 handles by the top, painted all over with an octopus decoration in black

Minoan clay vase with octopus decoration, c. 1500 BC

In culture

Ancient seafaring people were aware of the octopus, as evidenced by artworks and designs. For example, a stone carving found in the archaeological recovery from Bronze Age Minoan Crete at Knossos (1900–1100 BC) depicts a fisherman carrying an octopus.[132] The terrifyingly powerful Gorgon of Greek mythology may have been inspired by the octopus or squid, the octopus itself representing the severed head of Medusa, the beak as the protruding

golden eagles.[31] Since 1993, the eagles have caused the population to decline by as much as 95%.[30] Because of the low number of foxes, the population went through an Allee effect (an effect in which, at low enough densities, an individual's fitness decreases).[28] Conservationists had to take healthy breeding pairs out of the wild population to breed them in captivity until they had enough foxes to release back into the wild.[30] Nonnative grazers were also removed so that native plants would be able to grow back to their natural height, thereby providing adequate cover and protection for the foxes against golden eagles.[31]

Pseudalopex fulvipes

Darwin's fox is considered critically endangered because of their small known population of 250 mature individuals as well as their restricted distribution.[32] On the Chilean mainland, the population is limited to Nahuelbuta National Park and the surrounding Valdivian rainforest.[32] Similarly on Chiloé Island, their population is limited to the forests that extend from the southernmost to the northwesternmost part of the island.[32] Though the Nahuelbuta National Park is protected, 90% of the species live on Chiloé Island.[33]

A major issue the species faces is their dwindling, limited habitat due to the cutting and burning of the unprotected forests.[32] Because of deforestation, the Darwin's fox habitat is shrinking, allowing for their competitor's (chilla fox) preferred habitat of open space, to increase; the Darwin's fox, subsequently, is being outcompeted.[34] Another problem they face is their inability to fight off diseases transmitted by the increasing number of pet dogs.[32] To conserve these animals, researchers suggest the need for the forests that link the Nahuelbuta National Park to the coast of Chile and in turn Chiloé Island and its forests, to be pro

tongue and fangs, and its tentacles as the snakes.[133] The Kraken are legendary sea monsters of giant proportions said to dwell off the coasts of Norway and Greenland, usually portrayed in art as giant octopuses attacking ships. Linnaeus included it in the first edition of his 1735 Systema Naturae.[134][135] One translation of the Hawaiian creation myth the Kumulipo suggests that the octopus is the lone survivor of a previous age.[136][137][138] The Akkorokamui is a gigantic octopus-like monster from Ainu folklore, worshipped in Shinto.[139]

A battle with an octopus plays a significant role in Victor Hugo's 1866 book Travailleurs de la mer (Toilers of the Sea).[140] Ian Fleming's 1966 short story collection Octopussy and The Living Daylights, and the 1983 James Bond film were partly inspired by Hugo's book.[141] Japanese erotic art, shunga, includes ukiyo-e woodblock prints such as Katsushika Hokusai's 1814 print Tako to ama (The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife), in which an ama diver is sexually intertwined with a large and a small octopus.[142][143] The print is a forerunner of tentacle erotica.[144] The biologist P. Z. Myers noted in his science blog, Pharyngula, that octopuses appear in "extraordinary" graphic illustrations involving women, tentacles, and bare breasts.[145][146]

Since it has numerous arms emanating from a common centre, the octopus is often used as a symbol for a powerful and manipulative organisation, company, or country.[147]

Danger

Coloured drawing of a huge octopus rising from the sea and attacking a sailing ship's three masts with its spiralling arms

Pen and wash drawing of an imagined colossal octopus attacking a ship, by the malacologist Pierre de Montfort, 1801

Octopuses generally avoid humans, but incidents have been verified. For example, a 2.4-metre (8 ft) Pacific octopus, said to be nearly perfectly camouflaged, "lunged" at a diver and "wrangled" over his camera before it let go. Another diver recorded the encounter on video.[148] All species are venomous, but only blue-ringed octopuses have venom that is lethal to humans.[149] Bites are reported each year across the animals' range from Australia to the eastern Indo-Pacific Ocean. They bite only when provoked or accidentally stepped upon; bites are small and usually painless. The venom appears to be able to penetrate the skin without a puncture, given prolonged contact. It contains tetrodotoxin, which causes paralysis by blocking the transmission of nerve impulses to the muscles. This causes death by respiratory failure leading to cerebral anoxia. No antidote is known, but if breathing can be kept going artificially, patients recover within 24 hours.[150][151] Bites have been recorded from captive octopuses of other species; they leave swellings which disappear in a day or two.[152]

Fisheries

Main article: Octopus as food

Octopus fisheries exist around the world with total catches varying between 245,320 and 322,999 metric tons from 1986 to 1995.[153] The world catch peaked in 2007 at 380,000 tons, and had fallen by a tenth by 2012.[154] Methods to capture octopuses include pots, traps, trawls, snares, drift fishing, spearing, hooking and hand collection.[153] Octopus is eaten in many cultures, such as on the Mediterranean and Asian coasts.[155] The arms and sometimes other body parts are prepared in various ways, often varying by species or geography. Live octopuses are eaten in several countries around the world, including the US.[156][157] Animal welfare groups have objected to this practice on the basis that octopuses can experience pain.[158] Octopuses have a food conversion efficiency greater than that of chickens, making octopus aquaculture a possibility.[159] Octopuses compete with human fisheries targeting other species, and even rob traps and nets for their catch; they may,

Rüppell's fox

Red fox

Swift fox

Tibetan sand fox

The fennec fox is the smallest species of fox

Red fox

Conservation

The island fox is a near-threatened species.

Several fox species are endangered in their native environments. Pressures placed on foxes include habitat loss and being hunted for pelts, other trade, or control.[25] Due in part to their opportunistic hunting style and industriousness, foxes are commonly resented as nuisance animals.[26] Contrastingly, foxes, while often considered pests themselves, have been successfully employed to control pests on fruit farms while leaving the fruit intact.[27]

Urocyon littoralis

The island fox, though considered a near-threatened species throughout the world, is becoming increasingly endangered in its endemic environment of the California Channel Islands.[28] A population on an island is smaller than those on the mainland because of limited resources like space, food and shelter.[29] Island populations are therefore highly susceptible to external threats ranging from introduced predatory species and humans to extreme weather.[29]On the California Channel Islands, it was found that the population of the island fox was so low due to an outbreak of canine distemper virus from 1999 to 2000[30] as well as predation by non-native tected.[34] They also suggest that other forests around Chile be examined to determine whether Darwin's foxes have previously existed there or can live there in the future, should the need to reintroduce the species to those areas arise.[34] And finally, the researchers advise for the creation of a captive breeding program, in Chile, because of the limited number of mature individuals in the wild.[34]

Relationships with humans

A red fox on the porch of a houseDeligently with a distributed nervous system, and make use of 168 kinds of protocadherins (humans have 58), the proteins that guide the connections neurons make with each other. The California two-spot octopus has had its genome sequenced, allowing exploration of its molecular adaptations.[48] Having independently evolved mammal-like intelligence, octopuses have been compared by the philosopher Peter Godfrey-Smith, who has studied the nature of intelligence,[166] to hypothetical intelligent extraterrestrials.[167] Their problem-solving skills, along with their mobility and lack of rigid structure enable them to escape from supposedly secure tanks in laboratories and public aquariums.[168]

rban foxes have been identified as threats to cats and small dogs, and for this reason there is often pressure to exclude them from these environments.[50]

The San Joaquin kit fox is a highly endangered species that has, ironically, become adapted to urban living in the San Joaquin Valley and Salinas Valley of southern California. Its diet includes mice, ground squirrels, rabbits, hares, bird eggs, and insects, and it has claimed habitats in open areas, golf courses, drainage basins, and school grounds.[50]

In pop culture

Plate in the shape of two peaches depicting two foxes, Tang dynasty

Main article: Foxes in popular culture, films and literature

The fox appears in many cultures, usually in folklore. There are slight variations in their depictions. In Western and Persian folklore, foxes are symbols of cunning and trickery—a reputation derived especially from their reputed ability to evade hunters. This is usually represented as a character possessing these traits. These traits are used on a wide variety of characters, either making them a nuisance to the story, a misunderstood hero, or a devious villain.

Due to their intelligence, octopuses are listed in some countries as experimental animals on which surgery may not be performed without anesthesia, a protection usually extended only to vertebrates. In the UK from 1993 to 2012, the common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) was the only invertebrate protected under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.[169] In 2012, this legislation was extended to include all cephalopods[170] in accordance with a general EU directive.[171]

Some robotics research is exploring biomimicry of octopus features. Octopus arms can move and sense largely autonomously without intervention from the animal's central nervous system. In 2015 a team in Italy built soft-bodied robots able to crawl and swim, requiring only minimal computation.[172][173] In 2017 a German company made an arm with a soft pneumatically controlled silicone gripper fitted with two rows of suckers. It is able to grasp objects such as a metal tube, a magazine, or a ball, and to fill a glass by pouring water from a bottle.a

Dodaj komentar

Komentiraj